In the face of an ongoing pandemic, Strange Bird Immersive has elected to keep our doors closed. To help us

Category: Escape Rooms

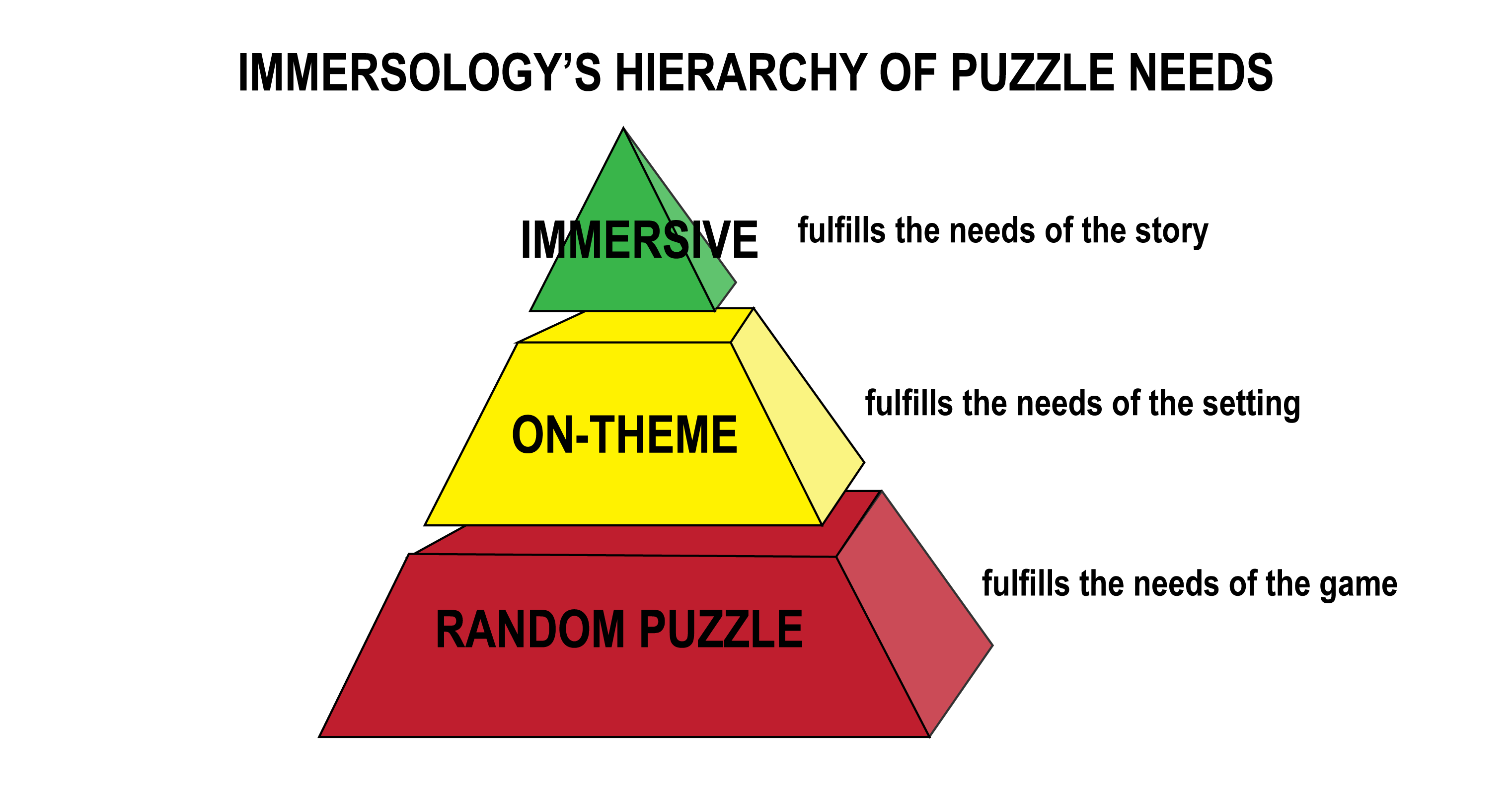

I’d like to propose a third category that goes beyond “on-theme”: is the puzzle immersive? An immersive prop or puzzle dives me deeper into the plot, character, or world. In short, when you step back to look at it, it makes sense.

While at the Transworld’s Room Escape Conference, I overheard the tail-end of another creator editorializing on an immersive experience he

My co-founder Cameron and I debated for too long whether we should attend Transworld’s Room Escape Conference. Considering we talked

Given the most innovative thing about immersives, “Rule #2: The audience is active,” it’s tempting as an immersive writer to

Big news hit the escape room community this week: Time Run announced their collaboration with BBC’s Sherlock in an all-new

Strange Bird has been receiving a lot of love lately from the escape room community, having recently won Room Escape

Two weeks ago, the Everything Immersive community was up in arms over a very serious safety infraction that resulted in

Tonight at 8 PM, Strange Bird Immersive celebrates its 100th performance of The Man From Beyond: Houdini Séance Escape Room.

This is gonna be a long one, but an important one, so strap in. It’s time to tackle escape rooms.

You must be logged in to post a comment.