As the date for this year’s virtual Reality Escape Convention approaches, I am getting HYPE by remembering my biggest take-away from last year’s in-person convention in Boston. It’s been in my head ever since. If you bumped into me in the past year, I probably waxed on a little too long about the idea. I love this idea. Time to share it more formally.

In a workshop entitled, “Reflecting your Business in your Brand,” Stuart Bogaty of Trap’t challenged us with the question of why we were in business.

He said there are typically three root whys…

- In it for the money

- In it for you

- In it for them

Stuart then asked us to rank these Three Whys by priority. Different businesses have different priorities, and ranking the three from most motivating to least motivating clarifies decisions that you’ve made—or will make.

Let’s dive in…

for the money

Money is the most obvious why. Most people labor for money. It’s a bonus if they enjoy the labor, but money is usually the primary goal. Small business owners are no different. Many start with the dream they might just strike it rich. The rest at least dream of replacing or surpassing the income of their more boring job.

It is not exactly a glamorous why. Who wants to be a fat cat capitalist when you could be a starving artist? *Commence wild eye rolling*

Let me push back against that idea. Money is an important why that (I swear) some people prioritize too low.

Yes, there can be a certain commercial sheen in a work created just for the money: it can feel shallow, passionless, rudderless, baffling the viewer into asking “Why does this exist?” Such experiences usually exit through the gift shop. But valuing profit does not guarantee that fate.

Profit and art can not just coincide, but should. Artists who neglect profit either stop being artists (we have to eat, too, you know), or depend upon a patron or outside source of income that, again, makes them and their work extraordinarily vulnerable. I abhor the notion that to make something that is profitable—that “the people like”—is to bastardize the purity of your artistic vision a priori. But I digress.

The degree of devotion to money can vary, from “maximize profit at all costs” to “as long as we’re in the black every month.”

Of course, go too far into maximizing your profits, and you diminish your product. That’s the story of most escape room chains. They prioritize growth to the point of destroying their product and thereby risk the entire escape room industry with their broken games and lost-at-sea game masters not even empowered to take a freaking SHARPIE to a prop where the Sharpie marks have completely faded!!!

“You can do it—fix it now! I’ll just stand here and wait! What do you mean, no?”

The Escape Game is a great example of a business that has money as its primary why, but hasn’t sacrificed the quality of its product in that pursuit. They understand that the best way to make money is to deliver a consistent product that delights a wide range of guests with best-in-class customer service. Rather than create new games for each of their locations, they perfect the ones they have—a cost-saving measure if there ever were one in this industry (I don’t know about you, but working on something new is so damn expensive). I recommend their games to locals and traveling enthusiasts alike.

You can tell that money is their goal because they went back to public bookings after the pandemic, which we all know makes for a weaker product but a better bottom line. But rumor has it if you contact them that you are an enthusiast who is (coughcough) likely to ruin other people’s games (cough), they may offer to make your booking private. Enthusiast money also speaks, apparently.

The Escape Game’s games will never top TERPECA, but they shouldn’t. That wouldn’t be in service of their top priority.

For you

Most small businesses owners could make more money working for somebody else. But that’s not what they want the most. They want something more—a challenge. They start a small business to serve themselves: to be their own boss, to do work they enjoy, to give themselves the space to showcase or grow their talents.

Maximizing profits rarely requires maximizing human potential, leaving so many of us bored and unexplored.

The world is crowded, and people are so creative. They have to claim their own space if they are to explore their creativity fully.

That is one of the things that made me fall so hard for the immersive arts. While the barrier to entry is not as low now as it once was, the immersive arts promises careers that previously were under lockdown, with only Hollywood and Broadway producers holding the keys. Start your own business, and look who’s holding the keys now?

Ever played a game where the creator wants to show you something in progress that they’re working on? Or give you a backstage tour? They always have such joy in their voice. I love it. That’s someone who is in it for themselves. Their self-exploration is what drives the business.

These types of businesses are called lifestyle businesses, as they exist to yield a desired lifestyle to the owner. Such owners may reach a point of contentment with their business, where it’s enough for them to maintain what they have. They don’t need to open new locations because adding more of the same work for more money isn’t a bargain that sounds attractive to these types.

Or they’ll go the opposite route, and it’s never enough. They will be always working on something new and something more ambitious than, quite frankly, it needs to be. But if you are ultimately serving yourself with your ambitious build, then maybe it is as ambitious as it needs to be.

If Felix Barrett’s recent press statement is to be believed, Punchdrunk has produced their last masked show with the closing of The Burnt City and will pursue new structures ahead. Which I think is wild—they have a model that works. But that’s what a business in it for the owners would choose to do. They’re bored. They crave what is new.

For them

Finally, we come to those who are externally motivated by them, whoever they are: the audience, viewer, player, customer. These creators will spare no expense to deliver something that truly wows the receiver. The sky is not too high.

It’s as if they are in the business of gift-giving.

Are they in love? I wonder.

These owners will be especially keen to receive feedback and adapt the product accordingly. They will want to make sure it works for the gift-receiver. They will often act irresponsibly when it comes to money.

People who prioritize their audience are how we get such indulgences as Molly’s Game and The Dome. Rumor has it neither will make their money back, but rumor has it the creators just don’t care. That’s not what they set out to do. They set out to blow your mind. That’s what matters.

Probably most TERPECA owners are them-motivated people. The games that make that list are irresponsible and off-the-hook.

Enjoy the gift.

My ranking

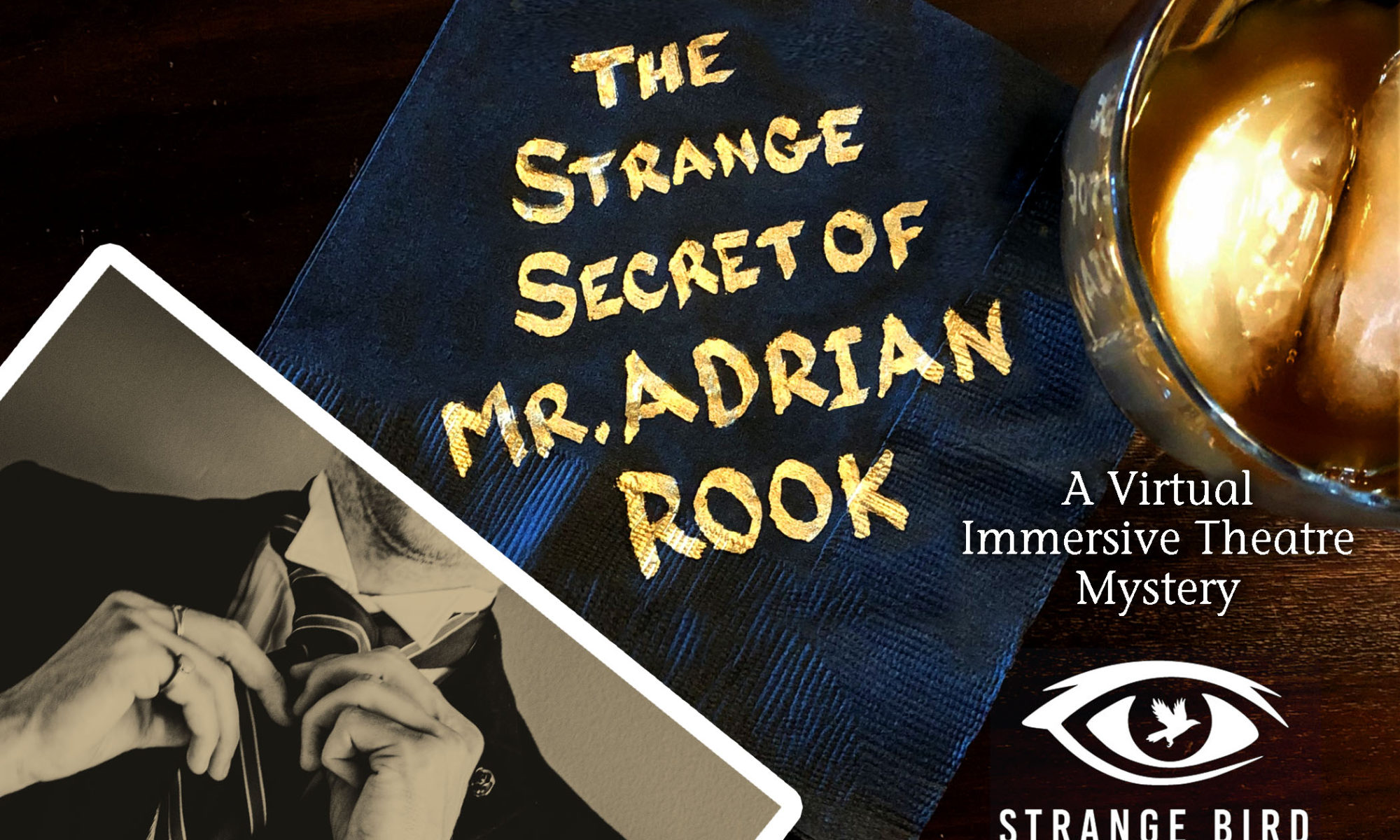

It will come as little surprise to my avid readers. For my part in Strange Bird Immersive, I am motivated by…

- Them.

- Money.

- Me.

I want to move people. I want to connect at the heart. I want to make my audience feel violently alive, aware of the full span of their lungs, flush with possibility. I want to do that so badly. And I will rewrite it if you don’t get that.

Perhaps the order of 2 and 3 was surprising to you? Where I ranked money surprised me, too. Fiscally, we’ve always structured our business to run a responsible profit, but I’d like to go further still in pursuing that value. Lucidity was designed at the outset to counter the fiscally questionable structure of The Man From Beyond—without sacrificing quality, of course.

It’s wonderful to create things, the sense of purpose I have every morning shoots me out of bed like a rocket, but at the end of the day, I am very open to replicating our experiences in other locations (that is, to make money), rather than always pushing the boundaries of what I can do. Opening other locations some day also serves my primary goal of reaching more people.

How to measure a successful business?

Once I had this lens at my disposal, I started to understand the wide variety of businesses out there. It has made me far less judgy of other people’s approaches. There are many ways to define a successful business beyond maximizing profits.

I’ve always resented immersive experiences that can afford to abandon all hope of making the investment back, as it makes those of us who don’t have that funding look weak in comparison. But nowadays, I feel less angry with the ones who can throw profit to the winds and more grateful that they choose to spend their money on me. So now I simply say, “Thank you.”

I also understand businesses that stop making new things, are not in the most optimal location, or are not doing particularly marquee-worthy things but are perfectly happy as they are. The owners are pursuing a life that makes them happy. Is that a bad business? No!

So next time you play a game or attend an immersive show, speculate on what their why might be.

And I encourage you to make your own list. Maybe it will surprise you, like it did me. It will help to step back and understand yourself—and may help you make your best business decisions yet.

Recon 2023

One of the best decisions you can make for any escape room business is to attend Recon this year, August 19-20, 2023. It’s virtual, so it’s easy to attend. I’m not paid to promote it or anything; it’s just a phenomenal professional opportunity I look forward to every year. The talks will be gold, but the connections more so. I would love to meet you at one of the extended “happy hours” in the wee hours of the morning and hear more about what motivates you.