(This post got buried in my drafts due to months of construction fun, so apologies for its not-quite-timeliness. I stand by its relevance, nonetheless).

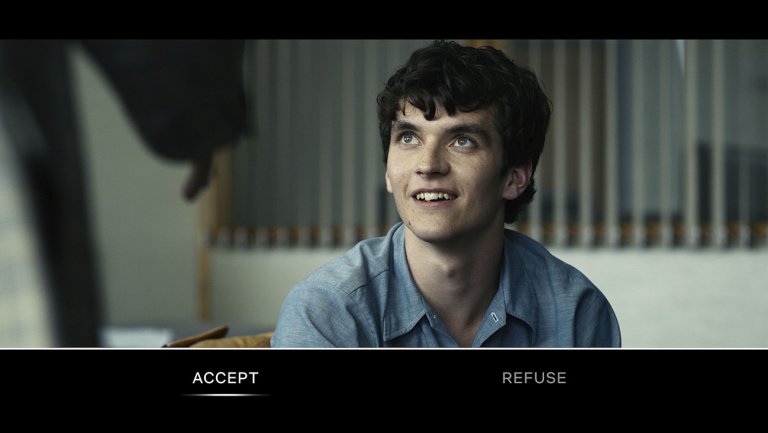

Cameron and I just wrapped up 85% of the decision tree of Black Mirror’s Bandersnatch (time to call it “good enough”), and it brought up a number of problems I’ve been thinking about regarding choice in immersives. Consider this to be a Bandersnatch meta-review.

If you haven’t played it yet, go do so. I’ll wait. Or not—I’ll limit spoilers, as what I want to examine here is the structural aspects of the experience, but note that reading this article beforehand may frame your experience of it.

Ready? Let’s go.

What do i want?

In a linear narrative experience, the kind we’re used to, no choice confronts the reader/viewer. If the writer even bothers to ask the recipients what they want, what it is they’re doing here, they’d probably answer “to experience the story.” Easy enough.

In a choose-your-own adventure (CYOA) scenario, the players need to decide what they want. Many stories are now available, so it’s not enough just to get to the end. You can go about blindly making choices, but I think a lot of players will want to construct some sort of strategy, and it will most likely involve maximization. Are we looking for the best ending? The worst ending? The wackiest ending? The ending most like what we would choose ourselves? (And, if it’s an option, some will play for all the endings, just on principle. I think Bandersnatch expects repeat plays, especially since you can get to endings pretty darn quick).

Be ready for your players to think in these terms. You should probably script endings to satisfy all of these types (spoiler: Bandersnatch didn’t, although I’ll concede that maybe that was their point…? More on that later).

Reality or fiction?

I find when I’m faced with choice in a narrative environment, I have two instincts: 1) do I take this as reality (when I know it isn’t), or 2) do I take this as fiction? These two perspectives have radically different outcomes.

If it’s reality, I’m likely to play more like myself. I’ll be honest, thoughtful, really reflecting on what I want at every decision point. I’ll want to draw out the good in other people, and do what I can to see my character to happiness. I’m also more likely to make conservative choices, because I don’t like frigging drama. Real people don’t want drama.

But if I take the world as a fiction, I’m going to want to flip some tables. I’ll be more inclined to make extreme choices, because extremity creates drama, and drama makes things way more interesting. But drama cracks a few eggs (or skulls), and you almost always pay a price for it. But hey! If it’s fiction after all, there are no actual consequences.

But immersives are a bit more social than reading a book or watching Netflix, so no, there are indeed consequences. People who approach the world as fiction tend to be the worst audiences in immersives. Actors, who have to believe, and players, who may choose to believe, will clash with the “it’s fiction” people. In my experience as a performer, I’ve found the “fiction” folks are the hardest to contain, because my character can’t even respond to them: we’re on different planes.

Adding on a choice-driven experience then gives a vehicle to maximize the blow-things-up impulse. Don’t be surprised when players take it.

BLACK HAT OR WHITE HAT?

Essentially, if you’re in a CYOA, you’re in Westworld. Do you take the white hat or the black hat path?

Given what HBO has shown us of the Westworld park design, it seems to me that the design itself encourages you to go black hat. The most exciting adventures happen when you buck the morality you practice in the real world. You’re rewarded for a lack of make-believe. (And of course only when the park is no longer consequence-free does the black hat path even look bad.) But are we really sure that inviting people to don the black hats doesn’t, in itself, have consequences?

I would think a designed experience that encourages black hatting does have consequences. The implication of so many rich people vacationing in a world without morality is an episode I’m still waiting to see. Are we really so certain of our ability to recognize the difference between reality and fiction?

I’m pretty sure I fell in love with immersives because my body couldn’t distinguish the difference, and my mind got a bit messed up because of it. They are fictions that truly happen to me. The black-hatting a CYOA inspires becomes a rougher, more visceral experience inside an immersive.

I found this piece on the original Club Drosselmeyer (Boston 2016) a very educational read: “On Drosselmeyer, devastating endings and giving your story to your audience!” On closing night, the winning group chose the “black hat” bad ending because they thought it’d be more fun. And everyone, from actors to participants who weren’t even aware such a choice was going on—had to experience the bad ending of Nazi victory. If you put a choice on the table, be ready to commit to every possible outcome.

I think a designer would be hard pressed to steer an audience entirely away from the “it’s just fiction, let’s see how extreme we can go” option. There’s always going to be someone wanting burn your world.

How do you design a choice-narrative that makes the “I’m taking this as real” path superior? Or even just appealing? I honestly think it’s easier to design an all-pro-black-hat experience, frankly, which is precisely what Bandersnatch does. Perhaps all CYOA experiences should embrace black-hatting.

I found myself in our first play-through of Bandersnatch going for the most dramatic path. It wasn’t explicitly “the most evil,” but I was all about not treating the characters as real people. If this had been an immersive, I would have been an incredibly obnoxious guest.

Story-litE

If you’re creating a multi-branching narrative, paths don’t share much overlapping information. There’s just not a lot of space for detailed narrative. I think that’s one of the reasons choose-your-own-adventure books didn’t take off: they were all too much the same.

I found Bandersnatch to be story-lite, a pseudo-intellectual piece who thinks it’s enough to say “choice” and “thief of destiny,” nod to the meta, and call it a philosophical day. Mentioning the issues is not the same as engaging with them, thanks. What’s worse: I didn’t care for the characters.

Can a fully-realized narrative exist in this format? Possibly. Every branch would need to share details with other branches or have their own unique arc. But the creators would have to show an interest in their narrative greater than in their decision tree. (And let’s face it, those choosing this format are super-into their decision tree).

Clear choices

In the first choice of major consequence, I hit a fast dead-end when I chose what the narrative wants me to choose. But it ended up being a choice that was incorrectly presented: “refuse” meant something different than I thought it meant. Choosing “accept” then proceeded to shame me for misunderstanding. While it trained me early in dead-ends and end-goals, I felt shamed by the creators for what ultimately was a sin of clarity on their end.

General customer service thing: don’t make fun of your players for their choices, and don’t bait-and-switch your choices on them. Unless of course you’re into that sort of thing. (Everyone’s got a fetish! Mine just happens to be making my guests feel like heroes.)

If you want me to feel ownership of a choice, be sure that I understand the options available to me. And make sure you signal to me that I’m making a choice. Bandersnatch didn’t have that problem because of the TV mechanism, but not knowing you’re making a choice is a common complaint I’ve heard when choice and immersives meet.

Choices that matter

The very first choice in Bandersnatch has no apparent consequence. It was a tutorial choice, but I still would have liked to see some reward, any reward for my action.

Every call-to-action in an immersive should give a reward for the activity. Period.

To our dismay, Bandersnatch continued to traffic in choices we had no opinion about. The screen presented what looked like similar actions. This left us in a constant state of shrugging. Sometimes they had no impact. More often, these indistinguishable actions ended up leading to very different paths, but again, I felt no ownership over them. It was just random. So why give me the choice at all?

Scaling choice

Cameron and I played together—and while we think a lot a like, two was too many cooks. I can’t imagine what it’d be like with a crowd. After the first choice, we paused and had a detailed discussion about how to play together with the mechanism. We decided to shout out choices so that the strength of our choice was communicated as clearly and as quickly as possible. Essentially, we wanted to limit debate but still experience it together.

I think the ideal player size for Bandersnatch is one. It’s on-demand video, it has no real estate limitations, no cost of goods sold, so that’s not really a problem.

I’m deeply skeptical of CYOA in immersive theatre because it leads to two options: 1) one person is capable of making the choice for the larger group (like flipping this switch), thus fundamentally dictating everyone else’s show, or 2) you have a jury deliberation moment. Is debating with other participants (whether friends or strangers) really that fun? And doesn’t someone usually get burned on a jury? People will either have no strong opinion (which means the choice is boring) or strong opinions where someone doesn’t get their way.

And you can’t have the jury moment take unlimited time, that’s just not practical, but putting a time limit on your jury deliberation moment will make players feel a lack of agency—the exact opposite of what you want to do by presenting a choice in the first place.

Or you can go with 3) a one-on-one-pipeline structure, much like Bandersnatch, and have one person making a choice only for herself. But that leads to some serious economic limitations since the through-put will never be high.

Play IT again?

Repeat customers is the Holy Grail for immersive designers, and choice seems to be the #1 tool for motivating the return. But how do you get audiences to pay to start at the beginning again?

We played Bandersnatch over two nights, but that second night bored me. We had to sit through a lot of content—unexciting content—that we’d seen before (and weren’t particularly excited by the first time) only to make choices we felt ambiguous about again.

To motivate a return, you need a ton of new content. And you have to make the depth of the content clear and present on the player’s first visit. They can spy that they could be on a radically different adventure. In short, if you’re banking on a return, you pretty much need to write a second show. Sleep No More justifies returns well. Escape rooms that promise more puzzles do not.

If you’re gating different shows by choice, you could also run into problems when repeat players face jury moments again. They’ll be desperate to make the opposite choice from their first visit but may lose the vote—and feel like they wasted their money.

The Man From Beyond takes a different strategy to repetition: we create an experience so detailed that returning is like watching your favorite movie again. We’ve had a surprising number of people return just for the emotional ride. No one cares that they’re repeating content because the content is exciting. Of course, we’re not building a business model on veterans, but I do think creating one amazing experience is more viable than housing a ton of content that most of your guests will never come back to see.

okay, but what did you really think of bandersnatch? (Spoiler section)

As far as decision trees go, it’s pretty clever. There’s a lot of clever going on. But witnessing somebody else’s cleverness is not why I seek the arts.

There’s a loop towards the end that a lot of people get stuck in, thinking there’s more, but there isn’t. They forced the black hat on me, and I couldn’t get out of the cycle. I looked on the internet, and saw there was no true white hat ending. Cute and all—apparently I don’t have the power to choose the best ending, just the illusion that it could be possible. This is in keeping with Black Mirror‘s general emotional goal, which is to shit on its audience.

Not a fan.

My efforts were rewarded when I hit the amusing meta-tracks (reminiscent of my favorite video game, The Stanley Parable, notably a CYOA). I laughed at those. But the story didn’t capture me, and I found replaying to be tedious work. At least if you have to see something again in Sleep No More, it’s usually freaking exciting!

I don’t think anyone wants to convert all of their storytelling to this form. But is film CYOAs a break-out genre we’ll see more of? I doubt even that. Bandersnatch felt like a gimmick instead of a pioneer.

the hard problems of choice

I get the impression that some immersive designers think increasing audience agency always makes for a better experience. I don’t. The Activity Spectrum is not qualitative. But I do think the more agency you grant, the more behaviors you need to prepare for, and I think the experience can very easily become unfulfilling. Like Bandersnatch.

If you’re designing with choice…

- Be ready for players to “black hat” your world and make choices just to watch the world burn.

- Don’t forget to write a detailed story for every branch. Choice is no substitute for story.

- Present clear choices—players need to know when they are making a choice and what each option is

- Give choices clear stakes and meaningful outcomes (that is, if you don’t want to jerk around your players)

- Design carefully for how many people make the choice. Having multiple people make a choice (the jury) or having one person choose for the rest (the rogue player) can be un-fun.

- If you’re banking on repeat customers, make it evident as they go through the experience that there’s a ton of content yet untapped

Which is to say, I’m a choice-skeptic. Some of these are hard problems.

I hear talk of CYOA-type things a lot, but I don’t even know of one that’s been produced yet, let alone played one. If you have, let me know. Let’s talk! Prove this skeptic wrong.

So what shape does / should agency take without injecting problematic degrees of choice into a narrative?

(Phenomenal read by the way, thanks for writing!!)

Good question, and something to think about. I don’t think choice is off the table! It’s just problematic.

I think the more you let a choice impact the experience (how deep are the branches? How often does a choice present?), the more problematic it gets. I’ve heard tell of escape room experiences that present a choice at the end, which is a good place for a choice that can be meaningful without some of the problems I’ve cited above.

Actions are my favorite form of agency and aren’t technically choice (at least in the conception of choice in this piece). I think inviting players to do something or say something has far fewer problems. Is that technically agency? Perhaps not. I also value presence and relationship, two great ways to invite the players into the world while still firmly controlling the strings of the narrative. I think “being seen by the story” counts more than “changing the outcome of the story” in this industry. But that’s my guess.

Being seen by the story… I like that!

And you make a very good point in that; agency really does come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Action and interaction really is often a much more gratifying experience than direct control of an outcome.

Back to your point in the piece, control over outcome then foists the responsibility of choosing on the participant(s). Even if you’re able to move through the logistical hurdles of granting them a legitimate, informed, choice… Do they really want that kind of choice?

Considering video games, the agency is in the creativity by which one arrives at what is -more often than not- a binary of outcome.

Which almost suggests the potential of a 3rd option for repetition and replay-ability, based on a variable outside of quantitative or qualitative content!