If you want to optimize for replayability, you have to look at why customers are coming to you in the first place. And the single most compelling feature of immersives is discovery.

Category: Escape Rooms

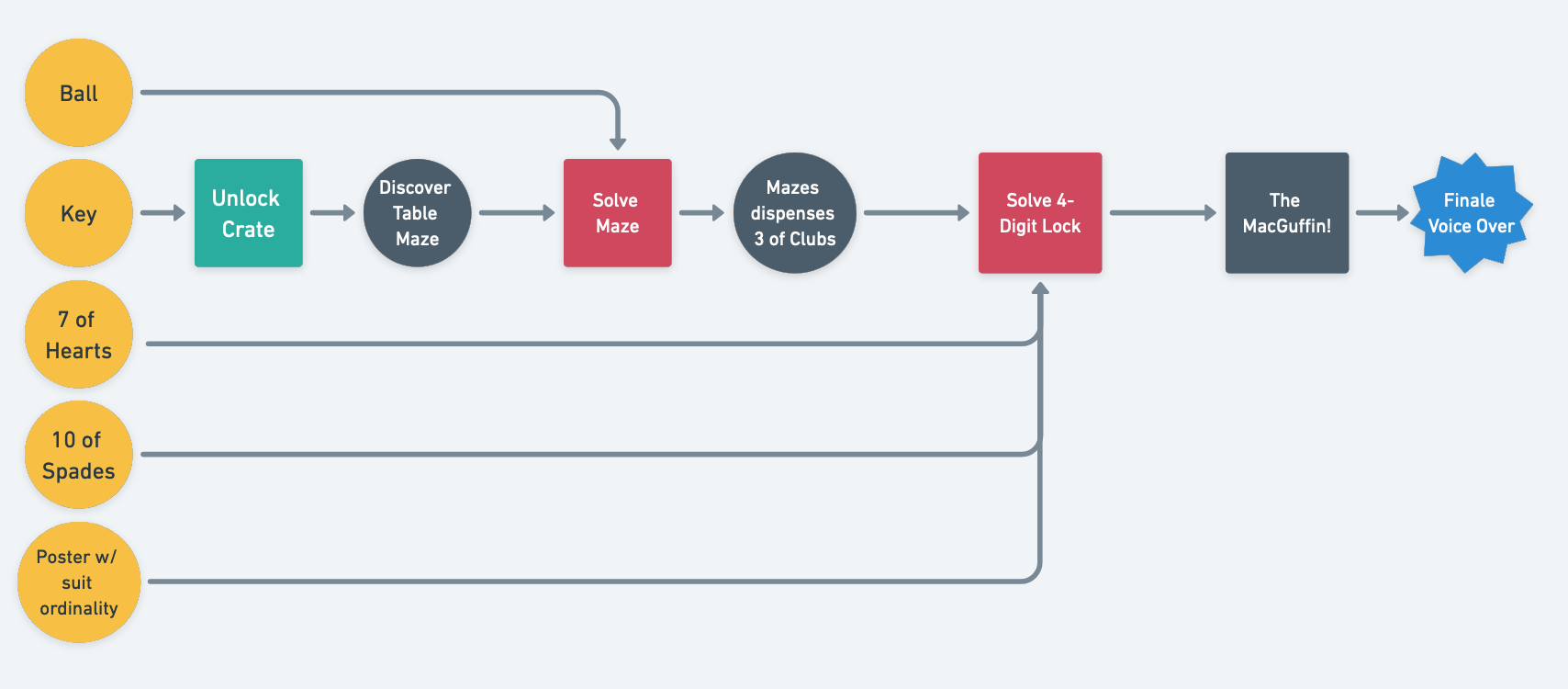

The player journey is an outline of your experience. It walks through the show beat by beat strictly through the guest’s eyes.

The Magic Circle’s magic is less about money spent on mechatronics and more about dedication in design.

There are many ways to define a successful business beyond maximizing profits.

When I played my first dozen escape rooms, I mapped them by hand afterwards, trying to make sense of the chaos: why did this game feel frustrating? Why did this game feel fun?

In Bookends and Bottlenecks, I explored the structure Strange Bird Immersive uses to tell stories within the chaos of an

In Bookends and Bottlenecks, I explored the structure Strange Bird Immersive uses to tell stories within the chaos of an

Showing the inciting incident makes escaping, obtaining the McGuffin—whatever the game goal is—meaningful. Telling the inciting incident results in a conclusion that has no weight.

The Strange Bird secret sauce is this: don’t put story and puzzles in conflict! Separate the two in the structure of your game, and then you can deliver both elements to the team’s complete satisfaction. We call the concept “Bookends & Bottlenecks.”

Words matter. Not to dive too deep into linguistic relativity, but words shape our ideas. They give ideas boundaries. They