In Bookends and Bottlenecks, I explored the structure Strange Bird Immersive uses to tell stories within the chaos of an escape room. I then specifically investigated the value of an inciting incident in an escape room. Giving players the motivation to act will make their achievement at the end of the game all the more valuable.

Let’s look now at that moment of achievement: the fulfilling finale.

Did you have fun?

Escape rooms have myriad goals: you need to escape the room, or get the McGuffin, or change something in the space, like lifting a curse. But no matter the goal, the ending is almost always the same.

Your Game Master opens the exit door and says…

“DID YOU HAVE FUN???”

No matter how on-point our GM has been through the experience, I absolutely loathe them in this moment.

Why?

They just cut my adventure short. They broke the magic circle of the world, signaled the end of the fun—not two seconds after the most thrilling moment of the game!

Imagine you’re riding a roller coaster, but right after the highest drop, the train suddenly stops, and the park employee says “Get out, its over.”

Escape rooms are phenomenal vehicles for emotions. They thrill us. We need time to come down from the climax.

THE WORLD MADE RIGHT

Something is wrong with the world in the game. (If you deliver an inciting incident like you should, the players will even see how the world gets all wrong). You then ask the players to make things right.

To be explicit, making things right feels great!

Players need time inside the world to enjoy their accomplishment.

If they helped a character out, show how things are now better for that character.

If they just saved the world, have the hint-mechanism character report back to the team the vast significance of what they did.

If they obtained the vaccine, maybe they disperse it into the air. Maybe they hear on a radio, walkie-talkie, or in-world TV about how many zombies are turning back to humans.

If players are escaping a serial killer, maybe you give them the opportunity to call the police at the end.

If players just got the key to escape the room (the simplest escape room story), let them open the door and rush into the hallway.

Find a way to remind the players of what was at stake and show the impact of their efforts. A conclusion will elevate your game from just another escape room into a froth-worthy adventure.

You know. Like that thing you sell on your website.

Take the time

The concluding bookend should be off the game clock. The players achieved their goal, and now they get to enjoy the fruits of their labor.

You can take as long as you want to end the story. It can take thirty seconds or much longer. I think the end of The Man From Beyond from climax to player exit is 15 minutes long.

I know this industry’s greatest pain point is throughput—we all have ceilings on how many games we can run on a Saturday. And I admit The Man From Beyond is too damn long for what we charge.

But concluding your narrative adventure should not be optional. I promise, you can do it without adding 15 minutes between your game times.

What about losing?

Readers of Immersology know by now that I have a very strong bias for designing escape rooms to be won by the vast majority, if not all teams.

But even The Man From Beyond has a losing scene. We hate running it, because the world is not made right again. But we do take the time inside the world to bring players out of the game, to come down from the high of “there’s one minute left on the clock!” In fact, one of our characters is made quite happy by the losing condition.

Write a losing ending. Don’t cheap out and have the Game Master come in. Maybe you can find a way to make losing fulfilling—often horror escape rooms are more interesting when you lose them than when you win! Yes, losing is no fun, you don’t get to feel like heroes, but a losing scene will bring the adventure to a close. Players will appreciate your commitment to the story.

A resolution by any other name would smell as sweet

In literary studies, endings go by many names.

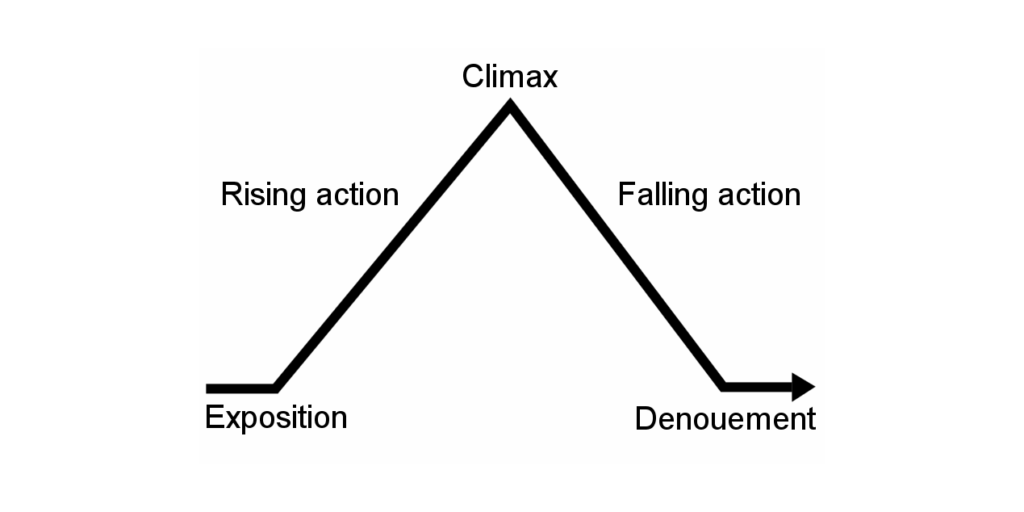

Fans of the linear Aristotle’s Poetics call it the denouement (French for “unknotting”). The world was knotty, but the conclusion unties the knot, re-stabilizing the world. It brings a quiet moment of peace.

Fans of the circular Hero’s Journey call it The Return: the moment the hero goes back home, but home is now different, after the hero’s transformation.

I like to call it the Fulfilling Finale. This phrase makes it clear what you need to do. I like the image of feeling full after a meal, not rushing up from the dinner table the moment you cleaned your plate. I also like alliteration a lot, and it pairs well with the pithy “inciting incident.”

At the risk of hubris, here is my map…

Note that the entirety of this map happens inside the imaginary world (aka the Magic Circle).

Whatever you call it, make sure your resolution accomplishes two goals:

One factual: How the world has changed.

One emotional: Come down from the climax.

A strong ending turns a game into a memory your players will carry with them. Stick the landing.

For more on escape room finales, check out Richard Burns’s article on Room Escape Artist, “Untie Your Escape Room Stories.” Let the reader note, Richard and I are actively searching for something we disagree about.