In Bookends and Bottlenecks, I explored the structure Strange Bird Immersive uses to tell stories within the chaos of an escape room.

The bookends of the experience are off-the-clock and where you can invest the majority of your story-telling, since there is no game to compete for player attention. I’d argue the beginning bookend is more crucial than the end, and could be the difference maker between just another escape room and an immersive adventure. Let’s focus on that beginning.

Most escape rooms take the easy way out for beginnings: they tell you the opening part of the adventure, whether through a game master reading a script or through a polished video. “You were wrongly imprisoned for a crime.” “You got lost in a cave.” “You awoke the tomb’s curse.” “The cat stole your keys and ran into the neighbor’s backyard!”

Wow, that sounds exciting. But note that word tell. No one likes being told.

What if we follow the mantra of all writing—and show rather than tell?

Most escape adventures start in Act 2 and skip Act 1. That’s like skipping the foundation of a house. It takes more work, but imagine how magical experiencing an inciting incident could be!

The game master takes you down a dark hallway where your team stands trial. An actor—or large projected video—of a judge sentences your team to life for murder. You have no idea what she’s talking about! You didn’t do it! Nooooooo!

The game master, now a warden, ushers you into your game: a jail cell escape room.

How much more motivated are you now to break out and find the evidence that ensures your innocence?

What if you’re touring a cave with your GM-turned-tour-guide, your lanterns flicker off, there’s sound effects of a cave-in, and when your lantern is restored, they’re gone? The GM yells through the “cave-in” (entrance door) and implores you to find another way out!

What if you’re poking innocently around a tomb door, and awaken the curse? You had no idea this place was cursed! (There’s so much magic in that moment when the supernatural first reveals itself.)

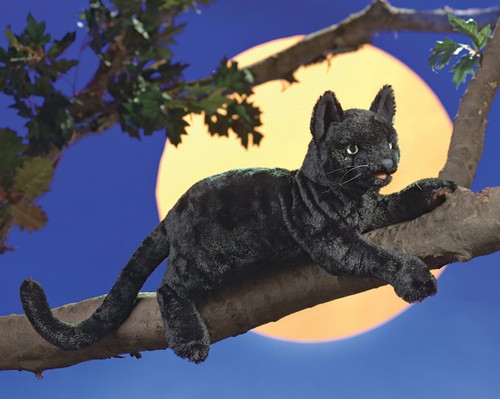

What if a cat-puppet appears from a tree hole, seduces you into petting it, and then steals your keys? Now you need to break into your neighbor’s backyard!

Are you having fun yet? I am, just imagining these games.

The inciting incident is the moment where something changes in the world that spurs our heroes (the players) to action. Without that moment, they could go about their lives, but with it, they must do something to right the world that will transform them into heroes.

All of these moments are moments of surprise. Escape rooms are all about surprise. And so are stories!

Showing the inciting incident makes escaping, obtaining the McGuffin—whatever the game goal is—meaningful. Telling the inciting incident results in a conclusion that has no weight. I can’t tell you how many games I’ve played that ended in “Yay…we got the…thing…that somehow helps a problem I’ve forgotten about…?” Things that happen to us have a lasting power that things told to us do not.

What about in media res?

In media res is a storytelling technique that plunges the reader/viewer into the middle of a story that has a long chain of events preceding it. It challenges the viewer to piece together what has happened before and gives the opening a strong sense of urgency. (Note that usually in media res still has an inciting incident for the plot. Think Luke finding the droids on Tatooine in Star Wars—the story doesn’t begin with the Empire takeover.)

In media res works if you are using the players as viewers. Think of Sleep No More: there’s no inciting incident for you, the viewer. You are not called to be heroic, nor is there anything you can do to help. The characters do experience an inciting incident…

But inciting incidents are necessary for the characters, not you, the guests. Immersive theatre can use in media res when the audience is purely passive, but escape rooms cannot, as the players are far more than viewers.

That’s what’s so cool about escape room stories. They are second-person narratives, first and foremost—you are at the center of the story, and what happens to the world depends on you.

You can encounter characters that are in media res in escape rooms, and that can make things exciting. But if you cast the players as previously-motivated characters rather than giving them the spur on the spot, they’re going to have trouble feeling properly motivated.

Where to begin the story?

In The Man From Beyond, Strange Bird invites you to a Houdini séance hosted by Madame Daphne. Then something goes wrong in the séance that has never happened before. You see it happen, and it is surprising. And because you are the ones who happen to be there, you have to do something.

The Man From Beyond starts at the beginning of your story; before arriving at Madame Daphne’s, your life was normal. We like to craft stories that hew close to reality. But what if you want a more complicated casting of the players and a less reality-based world?

In Hatch Escapes’s Lab Rat, you are cast as rat-sized humans in a human-sized rat world. How did the world come to be this way? They don’t show that—they don’t even tell that. But an event does happen that starts you on the adventure to save yourselves. That works great!

You can start at the moment that a usual world becomes unusual or from within an unusual world. Just because there’s been an apocalypse does not mean you have to show the apocalypse (although that would be very cool!). But at the very least, show the threat of the present world and then the moment of discovering that if we do X, the world will be better. That will really make me want to do X!

Whatever the role of the players, give the players the motivation to play—a narrative motivation that goes beyond “win/lose.”

How long to spend on the inciting incident?

The Man From Beyond spends 30 minutes on set-up and inciting incident (Act 1 in our five-act structure). That’s insanely long and a large part of what makes us a premium escape room. We specialize in immersive theatre, and our professional actors are exquisite.

I would not spend that much time on the inciting incident without live actors. Live actors (or live puppets—puppets are AMAZING—see cat puppet above) can hold attention better than any other story-telling vehicle. If you’re not using actors, keep your openings short.

It could be three minutes, or even thirty seconds. Just long enough to 1) set-up a normal world, and then 2) deliver the surprising thing that incites them to act. It doesn’t require a special room nor hiring more staff. You can incite on the cheap. But it does require special thought and must include a moment of surprise.

Design your inciting incident to your strengths and resources. And trust me. It’s worth it. Without experiencing an inciting incident, your players get only the shadow of an adventure. With it, and they will remember what they did that day.